A Sustainable Export Boom For Australia in Asia

How does Australia manage the twin challenges of coal exports to meet future energy demands in Asia with environmental challenges that have come to symbolise the industry?

In the International Monetary Fund’s 2018 outlook for Asia the authors highlight the astonishing rise of economies in this region over the last two decades. They attribute this achievement to a “winning mix of integration with the global economy via trade and foreign direct investment, high savings rates, large investments in human and physical capital, and sound macroeconomic policies”.

The large investments in human and physical capital have however afforded little attention to sustainability or the costs of economic externalities associated with these investments. As the wages and wealth of Asian countries have grown, so too have carbon dioxide emissions, loss of forests and habitats, and social dislocation. In pursuing the European and North American path to developed nation status, Asia has paid little attention to the costs associated with economic growth fuelled by coal (and oil).

Ironically, this unsustainable growth model, has proceeded in lockstep with global acknowledgements of the need to reduce carbon dioxide emissions at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) annual gatherings. With fast growing carbon emissions from Asia and limited will to reduce emissions by developed nations, the stock of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is projected to increase the global temperature and change the nature of life on earth for the people of all nations – developed, developing and undeveloped.

Pursuing policies and investment to uplift the living conditions of populous developing nations with no regard for the consequences of doubling carbon dioxide emissions, may have been well-intentioned, but it has failed to deliver sustainable development for Asia.

Australia and the rise of Asia: co-dependence on unsustainable development

As Asian manufacturing capacity has increased, Australia has extracted significant economic benefit from exporting its fossil fuel natural resources. Coal exports have increased from $9 billion in 2000 to $64 billion in 2019 (a tripling in real terms) and gas exports have increased from $2.5 billion in 2000 to $49 billion in 2019 (a more than 10 fold increase in real terms). Royalties from increased coal and gas production now provide comfort to New South Wales and Queensland state budgets; two per cent of revenue in New South Wales and seven per cent of revenue in Queensland.

The shift of significant levels of manufacturing capacity from developed countries to Asia since the 1980s, was premised on the expectation by developed countries that low-level manufacturing jobs should be transferred to low-cost developing countries, with higher-cost, developed countries shifting economic activity to higher order innovation, services, and consumption. Much of this has come to pass in Australia, as policies have focussed on education to foster innovation, and productivity to enhance competitive advantage. This focus has however concentrated employment gains in urban settings and encouraged reliance on the mining of coal and natural gas for regional development. Ironically, losing manufacturing capacity to developing countries, has made regional Australia more reliant on lower-order mining jobs and locked-in to an ideological view that fossil fuel exports are essential for economic growth and opportunity.

This urban-regional divide has fuelled a poisonous political debate about coal and climate change in Australia which has contributed to political instability. Prime ministers of both major political persuasions have been toppled, politicians have used the perception of urban-regional inequality to foster division for political gain, and action to reduce domestic carbon dioxide emissions has been whittled away. As long as Asian countries seek to buy Australian coal, little will change.

So, while Australia may have benefitted from directing investment to coal mining to sell increasing levels of coal to Asia, it has borne a cost from the increase of droughts, floods and bushfires that has resulted from increased greenhouse gases, and the cost associated with significant social division.

Policy to unravel unsustainable development

The common but differentiated responsibilities for carbon dioxide emission reduction as applied in the UNFCCC framework has not lead to sustainable development. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) came into effect after World War 2 primarily because the United States wanted access to Commonwealth markets and Commonwealth countries, primarily the UK, wanted access to US markets. The recognition of benefit from trade was enough for 22 countries to share in the USA-UK trade compact to commit to reduce tariffs in 1947, and corral in excess of 150 nations to adhere to GATT now. Is the way out of the impasse between national sovereignty, competitive advantage and emission reductions a return to agreements that derive benefit by providing access to markets?

There has long been discussion about the possibility for carbon border adjustments for countries or trading groups that commit to emission reduction. These measures are necessary to protect domestic industry that incurs the costs of abatement against imports that do not. The imposition of carbon border adjustments is a delicate business, with policy makers needing to tread carefully to adhere to fiercely guarded existing trade rules. The European Union’s recent announcement of The Green Deal and the consultation process for a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is the first serious attempt to incorporate carbon costs into trade agreements. The success of the CBAM will depend on its attractiveness to other major consumer markets, in particular Japan and the USA. If the major destinations for Asian manufactured product co-ordinate to be consistent in their approach to carbon border adjustments, there might just be enough critical mass to sway trade rules in the direction of sustainable development.

Conversely, if Europe’s CBAM fails to gain traction, reconsideration of a global carbon price, either as global emissions trading or a global carbon tax, will be necessary. Either way, the challenge would remain being able to reach agreement to targets to derive the cost of emissions. Will the threat of global climate change be enough to encourage global co-operation in addition to the competing concerns of nationalism and pandemics?

Back to the future with industrial policy

Amendments to trade rules to account for carbon emissions will encourage emission reduction in global trade and investment but attention needs to be given to national actions too. Since the global financial crisis in 2008 Europe has increasingly investigated the potential for stimulating regional development to counteract inequality and promote investment to achieve sustainable development through rebuilding disadvantaged regional economies.

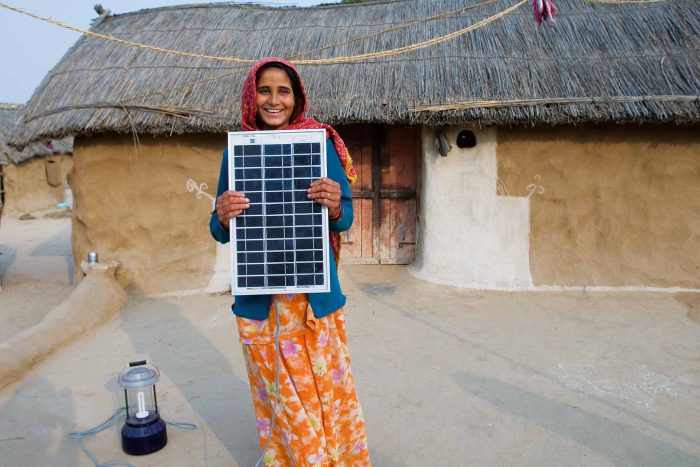

How might similar industrial policy benefit sustainable development in both Asia and Australia? There are a number of options. Firstly, investment opportunities to transition electricity generation from coal plant to wind and solar abound. All of Asia has a growing need for electricity. Capital costs of wind and solar have and will continue to reduce significantly, making investment in renewable energy in Asia and in Australia a rational mechanism for sustainable development. Reducing Asian demand for coal to fuel electricity generation, will reduce the incentive to invest in additional coal mining capacity in Australia, thereby soothing the political and social division that Asian demand for Australian coal has created. Industrial policy in both Australia and Asia that incentivises investment in renewable energy for electricity generation should be pursued.

Secondly, projections for electric vehicles (EV) indicate that their prices will equal internal combustion engine vehicle prices by the mid-2020s. Car manufacturers are racing to corner the EV market, so industrial policy across all of Asia in the form of incentives for investment in the car manufacturing sector to service domestic markets is already being pursued, and could be extended. Industrial Policy that facilitates a fast transition to EVs will improve health outcomes in large Asian cities and reduce the consequences of climate change on global agricultural production and population dislocation as a result of inundation from floods, sea level rise and bushfires.

Thirdly, as a result of exponentially increasing demand for energy storage for EVs and the need to firm and store electricity, the manufacture of li-ion (and other) energy storage is an attractive investment proposition. Manufacturers in China and South Korea are already demonstrating this by aggressively building energy storage manufacturing capacity. With deposits of many of the minerals required for battery manufacturing, the potential for low-cost energy from solar and wind energy, and the infrastructure to transport from mines to regional centres and then on to Asia, Australia is particularly well-placed to manufacture energy storage. Industrial policy in Australia should be focussed on attracting investment to Australia to benefit from this large global opportunity.

Fourthly, renewable hydrogen offers a tantalising new sustainable export opportunity for Australia. With low-cost energy sourced from solar and wind, renewable hydrogen can be produced in Australia and exported to Asia to fuel heavy and long-distance transportation. There is also talk of using renewable hydrogen for industrial applications like steel and aluminium manufacturing, but there is a counter-view – promoted by Ross Garnaut – that it is more cost efficient to use low-cost renewable energy in Australia to manufacture base metals like steel, alumina and copper and thereafter ship to Asia for production of goods. Notwithstanding the target markets for renewable energy, there is a real opportunity for Australia to continue to supply the world with energy products, but from renewable sources that promote sustainable development.

Meeting global commitments to Asian sustainable development

Australia, more than any other country, has benefitted economically from the rise of Asia. Asia’s pursuit of fossil fuelled development came at the cost of increasing pollution, and the world is now feeling the effects of climate change in response to fast increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Australia too has experienced droughts, bushfires and floods – a series of natural disasters as a result of an increase to the stock of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, predicted by climate modellers, decades ago.

The UNFCCC has consistently stated that richer developed nations should help poorer developing nations to transition their economies. As the Paris Agreement states: “To reach these ambitious goals, appropriate financial flows, a new technology framework and an enhanced capacity building framework will be put in place, thus supporting action by developing countries and the most vulnerable countries, in line with their own national objectives.”

How has Australia sought to support developing countries to reduce their emissions? Australian politicians who favour ongoing coal exports point to Australian coal being ‘cleaner’ than other suppliers, assuring vulnerable miners in regional Australia that exporting Australian coal to developing countries is good for the people in those countries. This sentiment peddles a double fallacy: that building power stations to burn coal will reduce pollution, and that coal-fired electricity generation improves the health of those who suffer from energy poverty. Employment in coal mining in regional Australia in effect leads to polluted Asian countries, and a destabilising global climate for all. Australia needs to lift its game and supply Asia with the affordable clean energy that it needs for sustainable development.