The Power of Parity in Asia: Improving Policies in the Workplace to Support Women Better

The goal of achieving gender equality in the workplace is not just the right thing to do; it makes sense for companies’ bottom lines and for the wider economy, particularly as the region looks to recover from the pandemic’s impacts. The good news is that corporate leaders can undertake a series of workplace policy changes that can make that goal a reality.

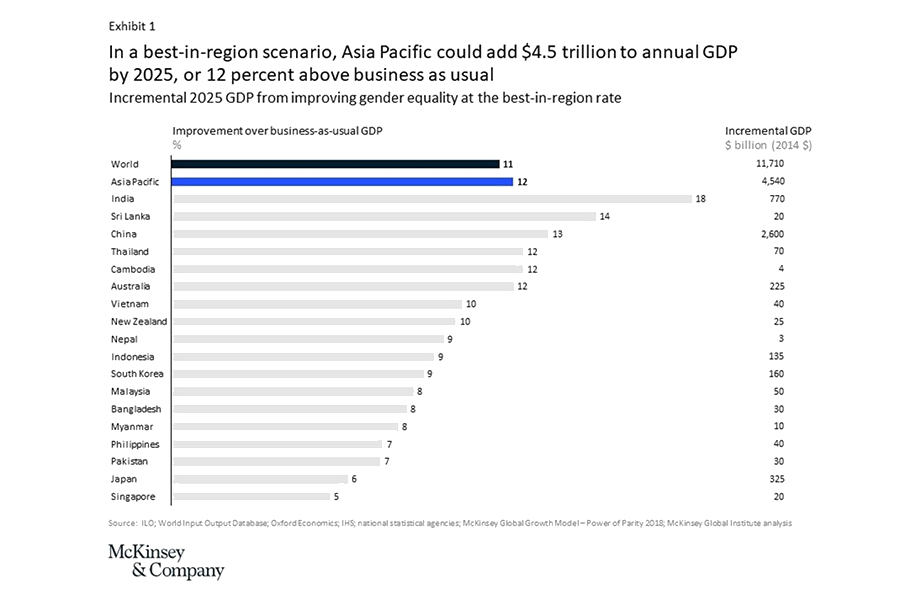

Advancing women’s equality in countries across Asia Pacific could add US$4.5 trillion to their collective annual GDP by 2025 – a 12 per cent increase over the business-as-usual trajectory. This statistic shows how important gender parity is for the region’s macroeconomic performance as it continues to wrestle with COVID-19. To realise this value, however, businesses, regulators and societies need to support women’s empowerment in the workplace.

Three economic levers are key to achieving this. First, raising the female-to-male labour-force participation ratio could contribute 58 per cent of the total GDP opportunity. Second, increasing the number of paid hours women work could create 17 per cent of the GDP opportunity. Finally, having more women work in higher-productivity sectors could contribute the remaining 25 per cent of economic value.

Exhibit 1

We have also found that the relationship between the diversity of executive teams and the likelihood of financial outperformance has strengthened over time. Analysis we undertook in 2019 found that companies in the top quartile of gender diversity on executive teams were 25 per cent more likely to experience above-average profitability than peer companies in the fourth quartile. With such strong business and societal cases for achieving gender parity, the time is now for companies to start making active changes in the workplace.

Asia has seen modest and uneven progress, worsened by the pandemic

Countries across Asia Pacific have made some advances in recent decades to improve gender equality, but overall progress has been modest and the results uneven.

In 2018, women made up 38 per cent of the labour force in Asia Pacific, contributing 36 per cent of combined GDP. By 2021, women’s participation in the work force has improved, but not everywhere. According to the International Labor Organisation, from 1990 to 2019, the female-to-male labor force participation ratio rose by ten percentage points in Japan and South Korea, nine percentage points in Malaysia, and five percentage points in Australia. But it has declined by six percentage points in China and by eight percentage points in India over the same period.

For both China and India, the decline reflects a complex web of related factors, including but not limited to challenges in accessing childcare, inequity in labour market conditions for men and women, and rising incomes. In the case of China, it is notable that despite the decline in labour force participation, women still contribute 41 per cent to GDP, the highest share in the Asia Pacific region.

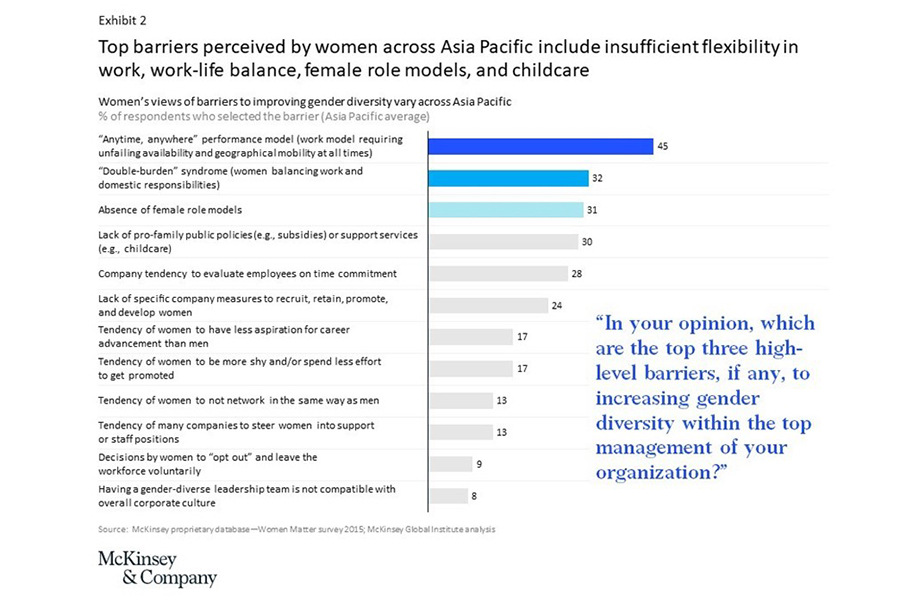

Before the pandemic, we asked 700 senior managers to find out what women thought was holding back gender parity. Some 45 per cent of the respondents said the biggest hurdle was the “anytime, anywhere” performance model, where companies require staff to be available and geographically mobile at all times. The next most cited barriers were the double burden of balancing work and domestic responsibilities, the lack of female role models and the lack of family-friendly workplace policies.

Exhibit 2

These challenges remain and have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis shows that during the crisis, jobs held by women have been 19 per cent more at risk than those held by men, because women are disproportionately represented in sectors negatively affected by the COVID-19 crisis. Women’s obligations to take care of their families have also increased, where for example in India, the burden of unpaid care and housework increased by around 30 per cent during the pandemic.. In South Asia, women’s share of unpaid care work can be up to 80-90 per cent. Our research found that there is a negative correlation between female labour force participation rates and unpaid care work. In September 2020, Australia reported that only 64 per cent of women with children under five years old participate in the labour force, compared to 95 per cent of men with children of a similar age.

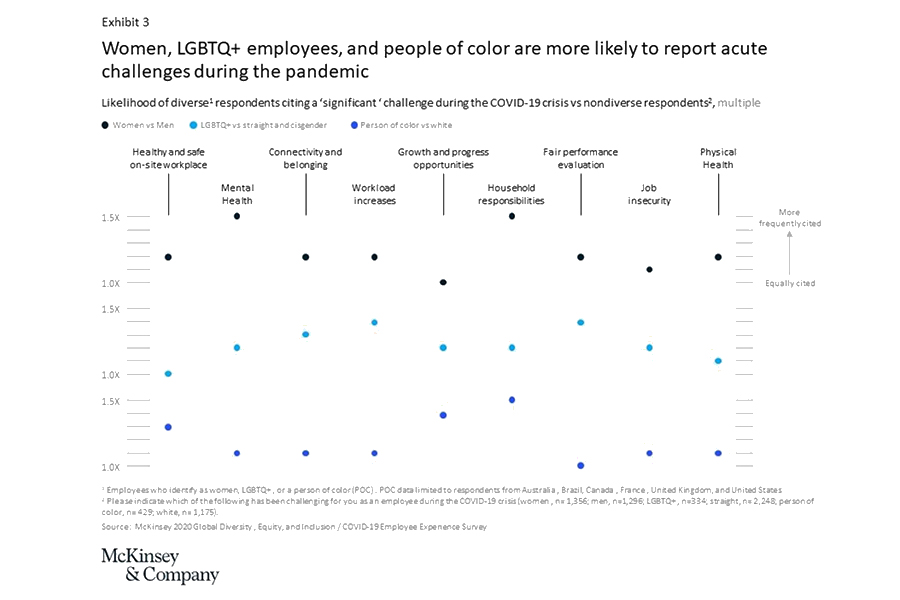

Women have also faced disproportionate stress through the pandemic. McKinsey’s global survey in 2020 of 1,122 executives and 2,656 employees across 11 countries including Australia, China and India showed that, in all geographies, women are facing more difficult challenges than men across personal and professional fronts during the pandemic.

Women are 1.5 times as likely as men to cite acute challenges with mental health and increased household responsibilities, as well as 1.2 times as likely to cite difficulties with workload increases, connectivity and belonging in the workplace, having a healthy and safe worksite, performance reviews, and physical health . In total, more than 60 per cent of women in emerging economies are suffering from acute or moderate challenges. This is double the rate of their peers in developed economies. Our survey also showed that a large share of employees expect workload increases to be an ongoing challenge.

Exhibit 3

This year, our annual Women in Workplace 2021 study, published in collaboration with LeanIn.org, reported that one in three women say that all these challenges have led them to consider downshifting their career or leaving the workforce, a significant increase from one in four a few months into the pandemic. Additionally, four in ten women have considered leaving their company or switching jobs and high employee turnover in recent months suggests that many are following through.

At the same time, women are still overrepresented in the informal sector: an estimated 58 per cent of employed women work in the informal sector, globally. These jobs are more at risk during the pandemic and without social or labour protections, and fewer benefits, these women face greater risk of disruptions to their livelihoods. The UN reports that workers in the informal sector lost on average 60 per cent of their usual income.

What it means for organisations to actively support women in the workplace

Our research is clear: first, what is good for greater gender equality is also good for the economy and society at large. Second, despite the difficulties brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected women more than men, we still see that women have risen up to the challenge.

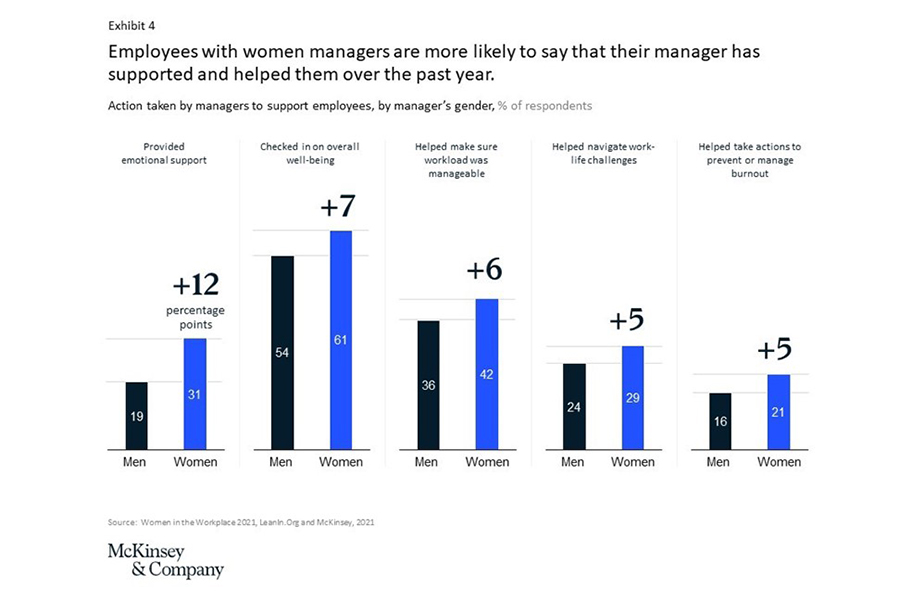

We found that women leaders have been stepping up and are doing more to support the people on their teams, for example, by helping team members navigate work–life challenges, ensuring that their workloads are manageable, and spending more time on diversity and inclusion work, such as recruiting employees from underrepresented groups.

Exhibit 4

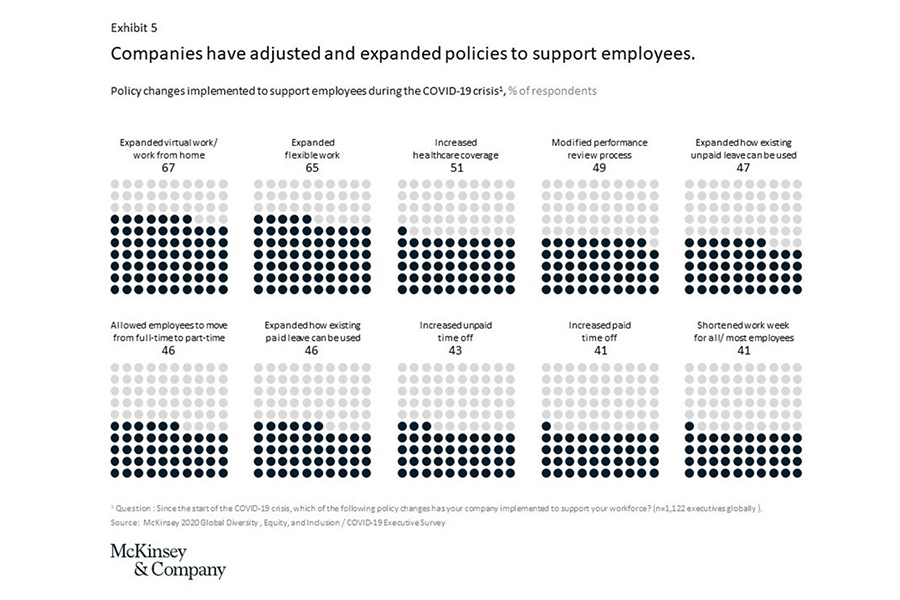

Many companies are also pursuing steps that can lay the groundwork for better diversity and inclusion. In our survey cited above, we asked executives how they have adjusted and expanded their working policies to support employees during the pandemic. The results show that, across the board, companies have undertaken changes that, together, have not only helped them to survive the pandemic, but which have formed a base for building a more inclusive and diverse workforce.

Our survey showed that around two thirds of companies have expanded their virtual, remote, and flexible working policies. Meanwhile, more than 40 per cent of companies had undertaken five more employee policy shifts, all of which could support a more inclusive workplace for women, even though the policies were initially aimed at supporting their overall workforce during the pandemic. These five are: allowing employees to move from full time to part time work, expanding how existing paid leave can be used, increasing unpaid time off, increasing paid time off, and shortening the work week for most if not all employees.

Exhibit 5

These working policy changes can form the basis of a push to increase inclusion and diversity in companies’ workforces. There are three key important levers – hiring, promotion, and retention.

Within hiring, there is a renewed importance for companies to expand their talent pools, build diverse candidate and interviewer slates, and ensure job descriptions, resume screening and interview processes are free from unintended bias. Companies can also consider workplace re-entry programmes for women who are looking to come back to the workforce.

To improve the promotion rates of women and ensure there are senior women leaders, companies can develop mentorship and sponsorship programs to help women build support networks needed to succeed. Companies can recognise and reward women leaders who are driving progress and doing deep cultural work to create an inclusive and valued workplace. Incorporating diversity analytics into succession planning processes can help ensure senior leaders are being thoughtful about roles and promotion opportunities for underrepresented colleagues. Finally, engaging managers and senior leaders in equity and inclusion-focused trainings can help them build muscles around recognizing bias and overcoming it.

Improving the retention of women and other under-represented groups has become especially important given the unequal impacts of the pandemic. Initiatives such as strengthening employee resource groups, expanding participation in leadership-development programs and, prioritising career-development planning have become critical to strengthening inclusion. Companies can also take bold steps to address burnout by building on some of the changed ways of working. A great example is the shift to technology-enabled remote working, which with its increased flexibility can facilitate retention of women. Finally, companies can also offer reskilling and upskilling programmes for under-represented employees to ensure retention rather than hiring of new talent.

Taking gender parity outside the office

Companies can also work to improve gender parity outside of their own offices. Some companies are asking their ecosystems (e.g., suppliers, contractors) to also work to improve the representation of women in the workforce by hiring more women and sourcing from women-owned businesses. Companies can also ensure their philanthropic or research efforts align with their diversity, equity, and inclusion goals.

Across all these efforts, it is important for companies to set measurable aspirations and goals around representation and levels of inclusion. These goals can be accompanied by visible support or public commitments from senior leaders, which further highlight the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion to employees. Progress against these should be monitored regularly and can be shared with employees or other stakeholders through townhalls or other forums.

The business case for inclusion and diversity is stronger than ever. For companies with diverse leadership teams, the likelihood of outperforming industry peers on profitability has increased over time, while the penalties are getting steeper for those lacking diversity. Although progress on representation in Asia has been modest, a few firms are making real strides. The pandemic has shown that it is equally important to strive for gender equality both when it comes to women in the workplace and generally in society. There is an opportunity to build on the changes necessitated by the pandemic to advance women’s inclusion in the workplace. There is a multi-trillion opportunity here, which must not be wasted.

Diaan-Yi Lin is a Senior Partner, Asilah Azil is an Associate Partner, and Aarthi Sridhar is a consultant in McKinsey’s Singapore office. The authors wish to thank Maria Martinez, Tiffany Burns, Sundiatu Dixon-Fyle, Kevin Dolan, Jess Huang, Mekala Krishnan, Alexis Krivkovich, Anu Madgavkar, Sara Prince, Ishanaa Rambachan, Irina Starikova, and Lareina Yee for their contributions to this article.