New Competitive Dynamics for a Climate Changing World

The world finds itself in unprecedented times. COVID-19 has presented a sudden disruptive shock, challenging the resilience of all major sectors of the economy and governments. Economies globally are in decline, supply chains are broken, students stranded, tourists grounded and demand for goods altered. In place of welcoming investment there is now growing concern about the implications of opportunistic investment by foreign companies in Australia.

As shocking as the events of the last ten months have been, we need to consider whether these challenges are potentially a ‘warm up’ to what is to come through climate change. If our systems and societies are disrupted by a pandemic, climate change has the potential to reorder the world.

There are some very real differences between our experiences with COVID-19 and climate change that will impact on future national competitiveness with implications for prosperity and security. The climate changing future brings with it significant direct physical impacts from the natural environment and indirect transitional impacts which are challenging on the socio-technical front. We have, however, an opportunity to invest now, to mitigate the change, building resilience and adaptation to limit the impacts. To understand the potential disruption to the Asia-Australia dynamic we need to consider both these direct and transitional impact areas. Firstly, we need to consider the biophysical impacts of climate change in terms of sea level rise, floods, droughts, storms and other extreme events, and the ability of nations to adapt and create resilience. Secondly, we need to consider how countries can change their industrial basis to deal with climate change and a transition towards decarbonisation.

The changing economic context

Competitive industries need to be created but also supported and sustained. Comprehending these processes is challenging on multiple fronts but necessary when considering the future of national industries and the companies within them. It is these dynamics which generate the wealth of nations.

The emergence and decline of industry has implications for the economic health of nations. So, what happens when you throw climate change and associated risks into the competitive dynamics mix?

The history of economics can provide insights into how extreme events and critical issues have been dealt with. In 1776 Adam Smith released The Wealth of Nations. Smith described ideal conditions through which economic prosperity could be maximised by a nation. Factors considered included: reduced levels of regulation, enhanced free trade, and nations developing their own specialist natural competitive advantage.

The long tradition of political economic discussion of these issues that ensued culminated in potentially the most relatable structure for comprehending the dynamics of national competitiveness in Michael Porter’s Competitive Advantage of Nations in which he formulated the Porter Diamond of Competitiveness.

However, the sources of competitive advantage remain controversial. According to neo-classical economic theory comparative advantages enables countries to compete sufficiently through factors such as an abundance of resources, their location geographically or through low cost inputs including labour. Noting that competitive firms clustered in nationally competitive industries, Porter generated a standard model for interpreting the dynamics of national competitive advantage. The Porter Diamond concept entails factor conditions, demand conditions, associated and sustaining industries, and firm structure, strategy and competitive rivalry. So deviations in national competitive advantage can be explained, for example, by examining resource abundance and consumption or faults in industry structure. Placed somewhat uneasily on the periphery of the Porter model are two conditions: the role of government, and chance.

We need to now consider how a changing climate sits in this model. How can we manage the impact on the structure of an industry where natural comparative advantages are now diminished? For example, through cycles of extreme drought and flood, or where industry is relocated through cattle production for export, or where there are changed societal preferences towards distributed energy production and manufacturing. How does this play out for communities embedded in established fossil fuel production areas given reduced financial investments and potentially reduced trade? The models of Smith and Porter were constructed on foundations where abundance and stability within the natural environment was not in question. What COVID-19 has demonstrated is the vulnerability and susceptibility of trade to these types of environmental jolts.

The climate-changed ‘Advantage of Nations’

It is undeniable the rapid economic transformation that has occurred in parts of Asia, such as China, over the last 50 years has generated wealth, national prosperity, security, trade and influence but it has also had a significant impact on the natural environment. Paradoxically, Asia simultaneously holds the title of the largest greenhouse gas emitter and also, in China, the largest installed capacity of solar and wind generation of any country. Challenges are faced in lifting populations out of poverty, indeed avoiding further poverty driven by climate change while promoting sustainable growth of the region’s economy.

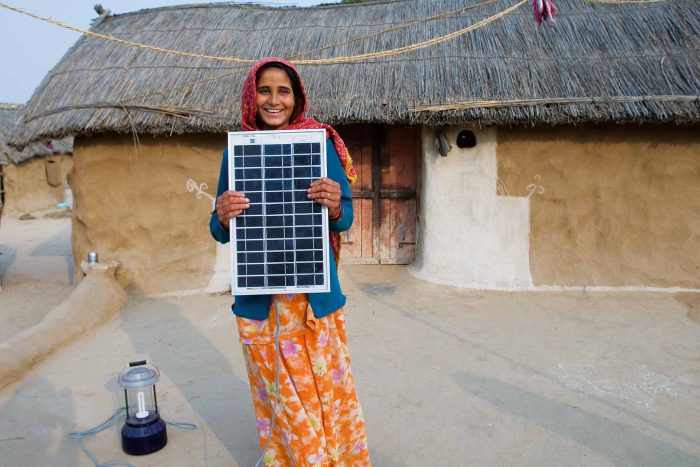

Evaluating new climate change driven dynamics must consider the transitional impacts including societal, technological, regulatory, legal, market changes. Clean technology will play a vital role in mitigating emissions, while also promoting adaptation and building resilience for a climate changing world. We now see some parts of Asia adopting a leadership role in renewable energy related technology development and manufacturing, supported by and supporting the country’s recent commitment to net zero emissions. Other nations within Asia, such as Indonesia and Bangladesh, are challenged by their rapidly expanding demand for energy, combined with affordability and reliability considerations. The clean tech revolution offers commercial opportunities for countries to reduce their dependence on coal, and drive economic growth through new industry sectors while mitigating the climate impact by reducing emissions.

China has announced global leadership ambitions in areas of technology, including green technology, urbanisation, energy and environmental management. According to the REN21 Renewable 2019 Global Status Report, in 2018 China was the world’s largest investor in renewables at US$91.2 billion (although this was a 37 per cent decline on the prior year). Renewable investment in Asia excluding India and China grew 6 per cent to US$44.2 billion. This investment compares favourably to Europe at US$61.2 billion and the US at US$48.5 billion. This long-term investment in technology and energy should be viewed as providing opportunities along these Asian countries’ entire value chain benefiting other sectors such as mining, transport, manufacturing, electronics, within their own and neighbouring economies. Stepping down from the national level there is no doubt that companies within Asia and Australia, through strategic action on climate change, can gain financial and thus also competitive benefits.

Providing for its own zero carbon transformation by prioritising clean tech investments can also give China a commercial leadership position as other countries race to net zero. Australia, without a net zero commitment, is yet to start the race and has to date largely relied on trade to provide clean technologies such as solar PV panels or electric vehicles. Increased discussions on advanced manufacturing in response to Covid-19 exposed supply chain vulnerabilities has the potential to promote increased clean tech manufacturing in Australia.

So where does this leave Australia if it can no longer depend on coal-related exports? Australia has a national competitive advantage in terms of space, research capabilities and natural resources. Metal and mineral resources other than coal, such as copper and lithium, will be required to fuel the clean tech transformation. An abundance of open space, wind and sunlight resources, combined with research and investment, provide a strong pathway for the generation and export of renewable based hydrogen and biofuels.

What might be called the climate-changing ‘Advantage of Nations’ has so far been built on understanding localised event impacts that have occurred over the long term, then supporting firms and sectors to develop targeted capabilities which they can use to meet challenges presented by these events. If we consider the situation of climate change, we need to accept that the unpredictable becomes the expected and capabilities of firms need to be urgently adapted under this expectation. This ability to adapt and build resilience to physical impacts of climate change is the answer to sustain long term competitiveness and trade.

While some companies in the insurance industry already research trends of extremes and their financial impact, to date the majority of corporate responses and discussions on climate change have focused on greenhouse gas mitigation. However the impacts from climate change already pose major challenges for organisational and industrial systems, particularly in vulnerable sectors and at risk locations necessitating action on adaptation and resilience. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that climate change related challenges for industries and society as a whole, come not only from the gradual atmospheric warming, but, from climate variability, including changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather. Conditions such as bushfire, flood and drought impact companies directly but also through challenging their access to insurance and options to manage the risk.

Organisation researchers and practitioners are yet to systematically evaluate the organisational implications of this increased volatility in the natural environment. Discussions on adaptation and resilience must be broadened, with novel conceptual and operational approaches required to incorporate the broader effects of climate change into notions of national competitive advantage. This will, of course, impact on trade.

In other words, in a climate changing world a focus on narrow sources of competitiveness and efficiency might hinder the need for governments and industries to build residual capacity – or slack – to cope with the risk.

A framework for determining climate adaption slack

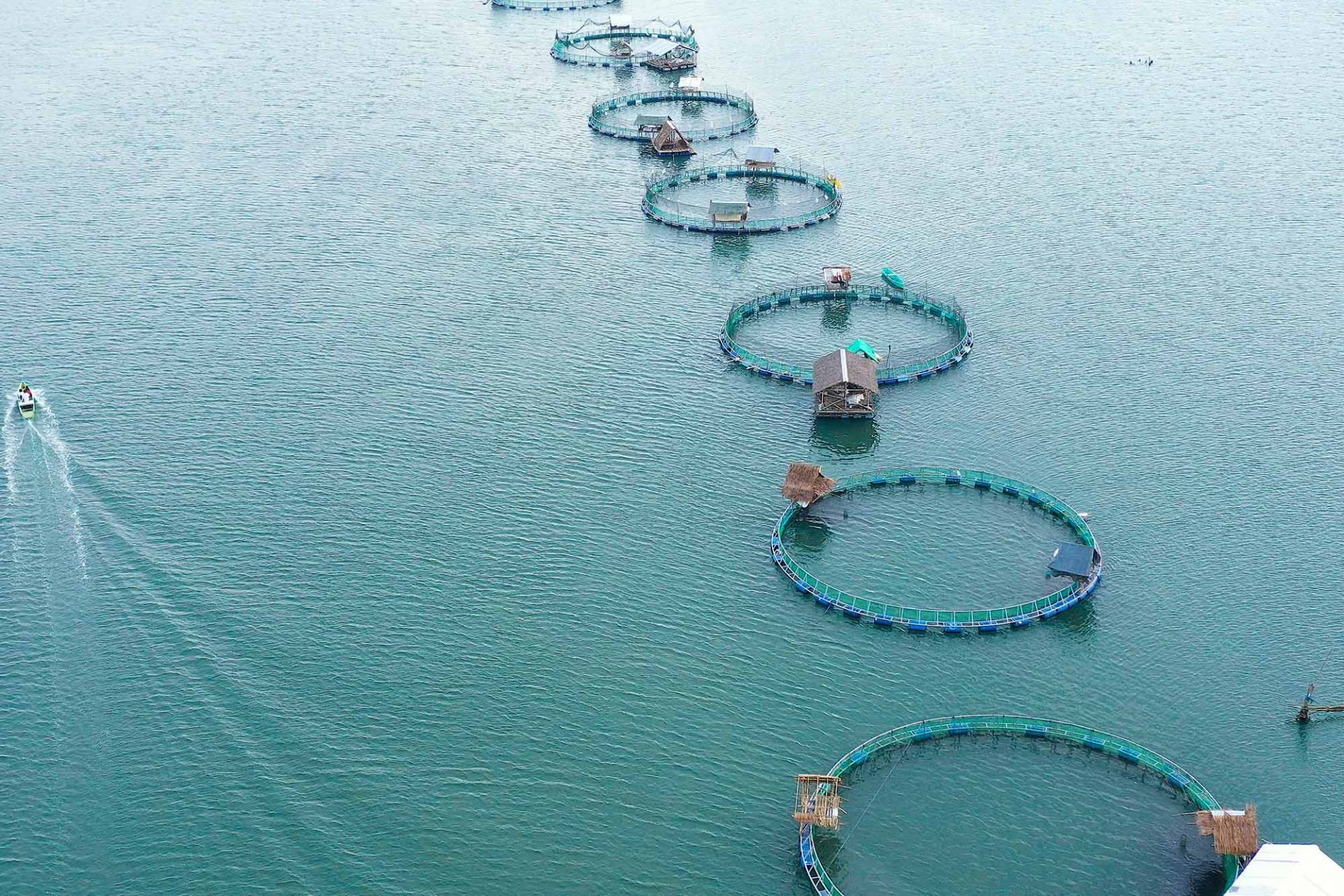

The ability of industries and firms to respond to extreme events will be critical to maintaining their own viability and success in a climate changing world. The concept of slack highlights the need to focus on providing industries and organisations with capabilities to pivot, allowing them to accommodate climate change related shocks.

Examples of climate adaption slack should be seen in a company’s supply chain; in the site choices of physical assets; in their emergency management planning; in innovation processes; business models; and hiring and partnering choices.

We propose that to achieve the desired outcome in terms of national competitiveness we need companies to build slack to promote climate adaptation and resilience at a firm and industry level, assisting in the creation of future national competitiveness and trade certainty. The following areas of capability development and action will become crucial in this endeavour.

Vulnerability Assessment

The ideal quantity of slack resources is dependent on the level of climate change impacts – whether they have become noticeable, are increasing and whether they have interrupted business operations. We argue firms need to do vulnerability assessments of their supply and value chains.

The higher the level of vulnerability to climate change, characterised by more significant and more sudden types of changes, the greater the necessary organisational capacity to adapt. Earlier, pre-emptive adaption and resilience-building is preferable to forced, sudden deviations.

Climate adapted site selection and management

Resilience can be built into operations by site selection, accounting for potential vulnerabilities to natural disaster, access to resources and supply chain disruption. It may be prudent to operate at multiple locations providing the ability to scale and contact operational output as required by disaster-related impacts and resource constraints. Offsite working, and additional sites for data storage, also promote operational resilience. Not all impacts from natural disasters are due to the disaster itself and can relate to poor infrastructure of site planning choices, as well as our own response to the disaster. In the Brisbane floods of 2011 significant damage and disruption was caused by the placement of building machinery in the basement areas of residential buildings.

Resilient business model by design

Integrating principles of the circular or the sharing economy into company business models can build resilience to some supply chain shocks by minimising the use of new resources. Establishing multiple markets for customer delivery and multiple points of value creation can support product resilience. During the pandemic we saw many governments, including Australia, intervene with financial support for workers and moratoriums on residential and commercial lease evictions. Climate related disasters, which are linked to specific locations are not likely to attract the same level of assistance. Companies need to build their own resilience.

Adaptive operation, production and delivery agility.

Recent experiences with COVID-19 have uncovered multiple areas of vulnerability across operation and production across nearly, if not all sectors. Vulnerabilities in supply chains, site access, connectivity for remote working, digitalisation, workforce redundancy to replace staff temporarily unavailability, and avenues for delivery were seen. These are all areas where companies need to consider building slack resource capacity in a climate changing future.

Digitalisation has been a focus of many companies, however the experience of COVID-19 brought into focus the functional resilience differences between companies with advanced levels of connectivity and digitalisation to those less advanced. Differences were apparent in their ability to reach new markets, for their staff to work remotely, and to monitor information and adapt. Countries with significant numbers of small and medium enterprises who may lack access to technology and market connectivity are vulnerable in a dynamic environment.

Over reliance on one transportation avenue such as air, rail or road may prove problematic during periods of disruption. Delivery agility is a vital capability in a climate changing future.

The climate changed ‘Advantage of Nations’ will be determined by the ability of industries and organisations to adapt so as to secure their competitive advantage over the long term through their capacity to understand impacts and to develop capabilities to address vulnerability at a firm level. The actions outlined here will allow industries and firms in Australia and Asia to contribute to national competitiveness of industries but also help sustain trade in a climate changing world.