Three Steps to a Sustainable Economic Alternative for the Asia-Pacific

As our region comes to terms with the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, we are faced with two stark options: struggling to return to business-as-usual or embracing a better alternative. We must choose the second option because humanity is changing and destroying nature at a rate unprecedented in human history.

While the business-as-usual approach that has seen the relentless pursuit of global economic growth since World War II has driven exponential human improvements, it has come at a significant cost to the Earth’s operating systems. This has led to a situation where humans are now overusing the planet’s biocapacity by at least 65 per cent. If we were farmers, we would be eating more than half the seed needed to grow next year’s crops. The old BAU approach is unequipped to deal with the new threats facing the world. “New and emerging threats – climate change, economic and financial instability, antibiotic resistance, transnational criminal networks and terrorism, cyber fragility, geopolitical volatility and conflict – simultaneously interact with development policies and actions to undermine gains”, according to a recent report from the UNDP.

The Asia-Pacific must be the centre-point of step-change towards a sustainable global future. A trilogy of transitions are already underway, and if fully supported, can be scaled to achieve a new-look GDP trajectory for the region, reversing some of the negative environmental and social impacts of relentless pursuit of growth. These three transitions are: utilise all mechanisms available to drive massive investment to “100% plus” renewable energy; harness technology innovations through scaling multi-sector approaches; and increase Official Development Assistance funds to be catalytic for a sustainable, fair and secure transition.

Business-as-usual will no longer work

The scientific and economic evidence for the growing rate at which we are destroying nature is unequivocal. The WWF Living Planet Report 2020 shows that populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish in the Asia-Pacific region declined by an average of 45 per cent between 1970 and 2016. From the largest to the smallest living things on Earth, nature is in serious decline. Meanwhile, humanity’s footprint across the Asia-Pacific has collectively risen dramatically in the past two decades – more than doubling.

The business-as-usual approach is unsustainable from an environmental point of view, but its disastrous impacts on natural capital also make it untenable from a future economic perspective. Biodiversity loss and climate change is fuelling rising inequality across our region.

A research partnership between WWF, the Global Trade Analysis Project and the Natural Capital Project examined the benefits that nature provides to all nations and industries through ecosystem services, including crop pollination, coastal protection, fresh water, marine fisheries, timber and carbon storage. It modelled how the natural assets that provide these services would change under various future scenarios. In a business-as-usual scenario, the reduction in these six ecosystem services alone would lead to a 0.67 per cent drop in annual global GDP by 2050, costing the world economy nearly US$10 trillion.

In 2020, economies are even more vulnerable. The World Bank reported that, when compared to pre-crisis forecasts, COVID-19 could push 71 million people into extreme poverty, concentrating a large share of the new poor in countries already struggling with high poverty rates.

All this is before we factor in the impact of reactive policy making that could take place in a post COVID-19 world, as governments face the challenge of balancing policy pivots in response to immediate economic shock, with longer term environmental projects whose social and environmental dividends will be vital for the future. Stunned by the impact of the pandemic, governments are facing enormous pressure to reverse or downgrade environmental protections and to reallocate funding from longer-term sustainable development projects that will pay dividends if they stay the course.

There must be a better option for people and the planet. And we must seize it.

Step one: More renewable energy

The first alternative opportunity is the transition of regional economies to “100%-plus” renewable energy. This move is already well underway and proving highly cost-effective. Renewable technologies like solar and wind, backed by storage, are now cheaper to build in most countries than coal power plants and other fossil fuel infrastructure.

Reducing carbon emissions reduces the ecological footprint of all people in our region, but it has multiple benefits. Renewable energy can reduce energy poverty by providing energy access and new jobs, reducing power bills, and addressing fossil fuel trade imbalances in smaller nations.

Asia-Pacific is both a laggard and a leader in clean energy. Japan is one of the most energy-efficient countries in the world and leads the charge towards renewable hydrogen. Malaysia and China are at the cutting edge of electric bus manufacturing, while China is a world pioneer not just in the annual deployment of renewables, but in the creation and commercialisation of new clean energy technologies. And with their recent announcement of net zero by 2060, China’s uptake of renewables is set to grow exponentially.

However, Southern and Southeast Asian countries lag behind the rest of the world, despite signals from Vietnam and India that effective policies can inspire the rapid growth of domestic renewable industries. In 2017, Vietnam had no solar industry to speak of, but the introduction of a target and supporting feed-in tariff saw 5 gigawatts (GW) of solar installed by 2020, far exceeding its 1GW goal. The story is similar in India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced in 2014 the need for “a saffron revolution that focuses on renewable energy sources such as solar energy, to meet India’s growing energy demand”. Solar and renewables played a very small role nationally at that time, but by the end of the decade 84GW of solar had been installed, making India one of the world’s fastest growing markets for renewables.

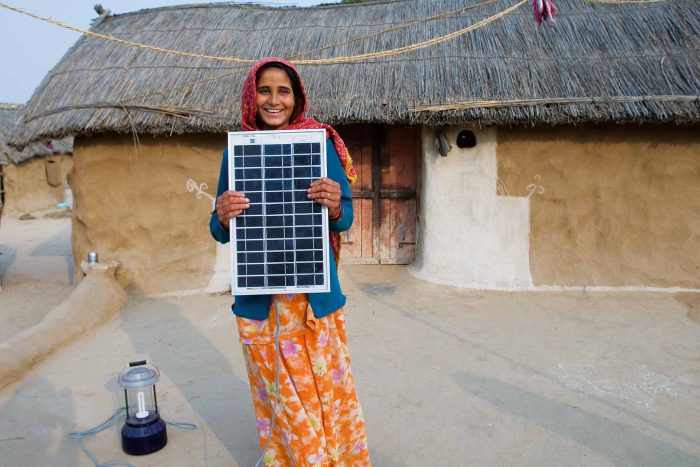

While large-scale renewables are starting to boom across Asia-Pacific, it is the modular integrated clean energy technologies (such as solar and battery storage) that hold the most exciting promise. With millions lacking access to reliable power, micro technologies such as solar lighting, solar phone charging and community-scale microgrids are helping to lift households in slums and remote communities across the Asia-Pacific out of energy poverty. In Indian villages lacking electricity, solar and battery models are powering new telephone towers, giving people access to new power as well as reliable telecommunications – a win-win.

Renewable technologies are making the promise of electricity equality a reality. However, if we are to tackle the climate challenge fully, we need to also look at using renewables to power heavy industry, manufacturing, and transport. Some Asian countries like Singapore may struggle due to land shortages. But others, like Australia, with world-class renewable resources and abundant land, are already looking at ways to help. Trade deals are being brokered for the export of renewable hydrogen from Australia to Singapore and Japan. And there is even a proposal – the Sun Cable project – to connect northern Australia to Singapore via an undersea cable and deliver solar power to Southeast Asia.

Australia has the potential to become a renewable energy exporting powerhouse, providing cheap energy to the region over the next decade. WWF-Australia has developed a framework for accelerating six renewable export opportunities as we commence the journey to “700% renewables”. “700%” renewables means shifting our existing electricity needs to renewables (100%), then going further and creating enough renewable energy to replace other fossil fuel processes and export renewable energy from Australia to the world. These include: renewable hydrogen, direct electricity transfer, solar power products, Australian expertise, components and recycling, and software and services. There is an enormous opportunity for us to create vast new onshore manufacturing industries and to export education and training. Momentum is building around this transition, transcending borders and party politics.

Step two: Embracing sustainable development

The second transition opportunity is to harness innovation around the United Nations’ sustainable development goals (SDGs). We are in the midst of a digital and technology-led disruption, where innovation is shifting from European and North American to Asia-Pacific economies.

Helpfully this decade, capital is flowing into to SDGs, but there is a mismatch between solutions and scale. We face a US$2.5 trillion funding gap to achieve the SDGs by 2030. This is not due to a lack of capital in existence. Rather, what is missing is a robust, efficient, and trusted mechanism for identifying and enabling projects that will advance the goals. Increasingly technology is providing solutions. Impactio, WWF’s latest social venture that serves as a global project curation and funding platform, brings together social entrepreneurs, experts, and financiers to develop creative and commercially viable projects that meet the SDGs.

This transition is the best manifestation of how companies can rally around sustainability without compromising financial returns. The past decade has seen a huge growth in “profit with purpose” enterprises and impact ventures. When coupled with purpose motives, technology is helping to eliminate earlier barriers to capital achieving positive ends. For example, transparency and traceability are enabling us to solve many of the illegal activities around commodities and natural resource conflicts.

One powerful global example of this is OpenSC. Driven by the belief that open supply chains are good for business, humanity and the planet, OpenSC is a social venture that spun-off in 2019, successfully raising US$4 million of seed capital from strategic impact investors in just its first year of operation.

OpenSC provides automated, data-backed verification of the sustainability and ethical production claims made by businesses across a range of industries. Among its clients are Nestlé and Austral Fisheries. A robust version of its technology platform is now complete and OpenSC has scaled up its solution for wild-caught seafood across Southern Ocean Patagonian toothfish and prawn supply chains, to help stamp out illegal fishing and human rights abuses. In simple terms, OpenSC uses its technology to give a new level of product visibility, tracing the journey from bait and paddock to plate. This helps consumers and businesses to make responsible decisions in support of producers who respect human rights and use environmentally sound practices. Ventures like OpenSC are showing the mutual benefits of good business, social ventures, and human rights advocacy.

The big opportunity for the Asia Pacific region comes at the larger intersection – between governments, local technology startups and civil society to accelerate global technology solutions around the SDGs. How do we accelerate the innovation capabilities across our region for scaling these multi-sector partnerships? These innovation-led collaborations are also at the heart of the third transition.

Step three: Restoring the role of development aid

The third transition is for donor countries to reverse the reductions in Official Development Assistance (ODA) in Asia, and instead establish a balanced and catalytic ODA portfolio that shores up the social and environmental safety net on GDP growth in the coming decades. ODA alone will not provide the US$2.5 trillion needed to achieve the SDGs, but the catalytic value of well-resourced, coordinated development assistance aid should not be underestimated. It plays a critical role – especially when blended with other capital and innovation – to finance the first two transitions.

When we look at Australia, it has – in the face of unprecedented crises in its immediate region – reduced its aid budget to historically low levels and cut staffing and operational budgets for its diplomatic corps. These cuts were designed for a pre-COVID-19 world. For Australia to effectively take advantage of the opportunities to make a difference, it should instead commit to reaching ODA spending of 0.5 per cent of gross national income in no more than five years and 0.7 per cent by 2030. It should make additional investments in international climate finance and bilateral cooperation and reinvest in its diplomatic corps to enable greater engagement with important regional bodies, including the Asian Development Bank, ASEAN, Green Climate Fund and Pacific Islands Forum. This reinvestment into ODA should also support greater collaboration between the development, diplomatic and defence communities. This final transition would increase regional prosperity and stability and improve diplomatic relations by ensuring that sustainable development is at the heart of regional relationships.

Australia’s role in the Pacific

This trilogy of transitions is not just what we can accomplish as a country, but what we can take to the world. Australia has the potential to play a leading role in extending these transformations, most notably to the Pacific, where the benefits could be enormous. Climate change and the overexploitation of regional fisheries are two significant challenges facing Pacific Island nations. If Australia were to realise its potential to become a renewable energy powerhouse it could ease the current diplomatic tension with Pacific Ocean nations over our refusal to exit from thermal coal exports, enabling us to substitute renewable hydrogen for coal shipments to Japan, Korea and China. Innovation technology solutions, coupled with low-cost renewables from Asia, can remove the ‘diesel fuel dependency’ economic yoke from Pacific Island countries, while also addressing energy poverty in small island communities, bringing both treasury and sustainable development benefits. As an example, the implementation of blockchain-enabled traceability platforms in Pacific tuna fleets could stop illegal, unreported and unregulated fisheries, increasing treasury revenue, reducing the dependency of Pacific Island countries on aid, and improving regional security around natural resources.

The WWF Living Planet Report 2020 paints a bleak picture. However, there are many reasons for hope that the next decade will not be the same as the last. In the new world of COVID-19, the outdated business-as-usual approach is no longer viable. We must do things differently by political, economic, and environmental necessity. We have also reached a unique moment in time when technology is at an inception point to transform the way we achieve truly sustainable development. We are all, indeed, in this together – to meet the current COVID-19 challenges but also the more enduring planetary crises we face.