Engaging Asia’s State-Owned Enterprises in the Climate Challenge

The government is back in business. With eye-watering levels of sovereign stimulus spending in the wake of the COVID-19 economic crisis, this statement may be truer today than it has been for a long time. However, quite aside from stimulus, the government remains a significant direct actor in the economy too, through state-owned enterprises (SOEs). These government businesses remain prevalent all over the world, and particularly in Asia, and the way they respond to global climate change matters to Australia.

Size and significance of SOEs

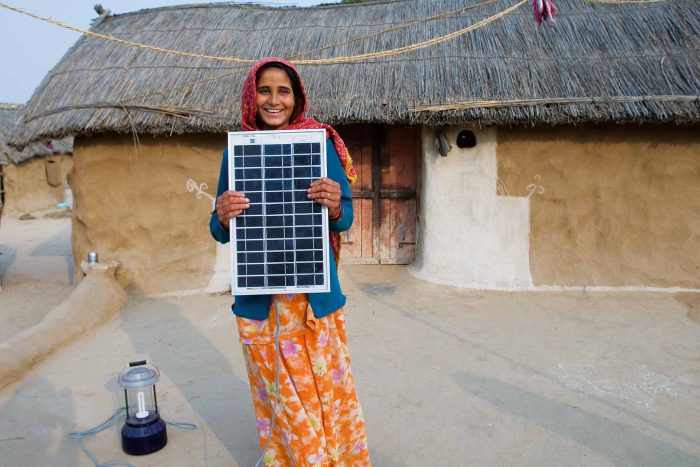

SOEs are corporations which a government (and ultimately the public) owns in full or in part. Historically, they were created to respond to major economic shocks (like the Great Depression and the oil shocks in the 1970s) and geo-political shocks (such as the World Wars). Snowy Hydro Limited, the company which runs Australia’s largest hydroelectric power plant, for example, is a wholly government-owned SOE set up to provide economic stimulus after World War Two. These companies also operate to provide goods and services which private market actors are not motivated to provide. For instance, many governments use SOEs to provide infrastructure, subsidised electricity or water services to the publics they serve.

These government-owned companies went out of fashion in Western liberal democracies in the 1970s, as neo-liberal economic policy was popularised and politicians sought to shrink the size of government. Postal services, public transportation infrastructure and electric utilities among others, were sold off to private investors. In Asia, where SOEs were particularly prevalent, multilateral development finance institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, encouraged privatisation too. This recent history of SOE reform, has led many to believe that the state sector is no longer a significant player in the global economy.

However, despite waves of attempted reform, SOEs continue to exist in large numbers, and have grown in significance in the global economy in recent years. In many countries, reform efforts were never completed or were wound back. Perhaps more significantly, countries with a large state enterprise presence – such as Brazil, China, India, South Korea and some countries in Southeast Asia – have grown dramatically in the past three decades. Consequently, the proportion of SOEs among the Fortune Global 500 list has grown from nine per cent in 2005 to 23 per cent in 2014, including a greater presence of such companies at the top of the rankings. The most profitable company in the world in 2019 – Saudi Arabia’s Aramco – is an SOE (not a private company like Apple or Amazon). And in some sectors, like energy, SOEs account for a larger share of the sector than private corporations do.

Asia is the home of a significant proportion of such SOEs. Chinese SOEs are perhaps the most well-known. They feature prominently in Australian media, because they have invested heavily both within and outside the country and because of the significant trade relationships Australia has with such firms. But state-owned firms are active players in countries across the region. In India, some of the largest electric utilities are owned by the federal government (the National Thermal Power Company) and state governments. In Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore too, SOEs are prevalent across sectors. For instance, in Singapore, a government holding company, Temasek Holdings, which is owned by the Ministry of Finance, manages the state’s government-linked companies across the electricity, telecommunications and finance sector.

How state enterprises contribute and respond to climate change

The growth in the scope and scale of these companies in Asia and across the global economy is significant for several reasons. But it has particular, and perhaps underappreciated, significance for climate change. SOEs are both major contributors to global emissions and are subjects of the physical, economic and public policy consequences associated with climate change.

SOEs are among the world’s largest corporate emitters of greenhouse gases. As colleagues at Columbia University have recently pointed out, SOEs in the power, industry and transport sectors alone emit an aggregate of 6.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent annually, making them cumulatively larger emitters than any other single country except China. In the power sector, 62 per cent of all power generated comes from SOEs. This means that reducing global emissions from the power sector – the single largest sector for emissions – requires these state firms to innovate and adopt cleaner low-emissions sources of power generation (watch this space).

In addition to being major contributors of global emissions, SOEs are also exposed to its effects. SOEs manage and invest public capital, they are stewards of public land, and they deliver goods and services like water and electricity, ports, housing and other major infrastructure. Each of these assets are likely to be impacted by climate change. For instance, infrastructure may bear the brunt of increased weather events. These impacts of climate change on SOEs are particularly important because the ultimate shareholders of these firms are members of the public. If SOEs do not proactively manage their climate risk exposure, then members of the public will be left to suffer the financial costs of doing so.

Additionally, because of climate change, public financiers may be invested in assets which become “stranded” because of changes in energy markets. Coal demand, for instance, which was already falling in some markets prior to COVID, has fallen off a cliff globally and is being offset by increased demand for clean energy. This means that some SOEs will be left holding technologies which can no longer be used consistently with policy or market demands. For example, colleagues at Oxford University’s Smith School for Enterprise and Environment have shown, how Chinese SOEs may be significantly overinvested in coal-fired power assets.

A strategy for Australian government engagement

Australians who have seen significant privatisation across this country might wonder why they should care about SOEs. There are at least three reasons.

Firstly, despite waves of privatisation, Australian governments at the state and federal levels still manage hundreds of these companies. They carry out a range of activities, including managing natural resources, providing water and electricity, and financing new infrastructure. As I and some leading Australian lawyers have pointed out, senior managers of those companies may be subject to obligations to manage climate risks. Indeed, some of these companies have already come under legal scrutiny to do so.

Secondly, beyond Australian shores, there are clear links between SOE responses to climate change and the impact on Australian industry. On the positive side, Australian businesses are benefiting from growing demand in the region for renewable energy. Sun Cable, the major project which will export electricity from the Northern Territory to Singapore, will provide power to SOEs in the region, including potentially in Singapore and Indonesia. The more power sector SOEs in the region understand that reducing emissions is in their interest, the more projects like these, or those which may emerge under a hydrogen export sector, will benefit.

However, the way that SOEs respond to climate change, will also have negative impacts on Australian exports. Consider China, for instance. That country’s recent announcement of emissions peaking by 2030, and a net-zero emissions commitment by 2060, raises the possibility of long-term structural decline in coal demand. Indeed, work by the Chinese government-controlled Energy Reform Institute suggests that even under their currently stated policies and existing capital stock, Chinese SOEs will need to halve the amount of coal they use in the electricity system alone by 2035. These changes could have major impacts on Australia because China is one of our largest coal export markets.

Further, the Australian financial community might also pay more attention to this issue. Although some SOEs in Asia are wholly government-owned and do not have any exposure to private capital markets, there are many large partially privatised SOEs (for instance, Japan’s TEPCO, Korea’s KEPCO and India’s NTPC) which include foreign equity investors. Many wholly government-owned firms also raise money for their operations through global debt markets. Australian institutional investors should evaluate and ask more questions about climate risk exposure when investing in sovereign bonds which finance SOE activities. Recent work by colleagues at the Brookings Institute has shown how, in the US context at least, there is a major disconnect between climate risk exposure and disclosure to the market of such risks. The same situation is likely in Asia, exposing creditors to company risks.

Thirdly, Australian climate change-related not-for-profits and researchers could work more closely with SOEs in the region. Leading Australian organisations, like Climate Works, already have deep expertise on some of the region’s SOEs and their possible role in managing climate change. Australians should not underestimate the ability of not-for-profit institutions to have influence on issues where it may be difficult or sensitive for Australian governments to engage. For instance, the Centre for Policy Development (CPD) has for several years run the Asia Dialogue on Forced Migration which works as a second track process alongside the government-led Bali Process and the Association of Southeast Asian nations. Through this forum, CPD brings together governments and civil society to work constructively on a highly sensitive set of issues. A similar effort by Australian civil society, working with, for instance, ASEAN’s power utilities authority (HAPUA) could go a long way to embedding climate risk and responsibilities into SOE activities in the region.

Government-owned businesses have gone out of fashion in Australia. But they remain important players in our economy and in the region into which we have significant trade and investment relationships. The way these companies respond to climate change over the next decade will play a more significant role to the livelihoods and quality of life of Australians than many might realise.