Australia’s Opportunity In A New Approach To Asian Waste Management

Along the Ciliwung River in East Java, small craft villages are quickly becoming home to informal recycling centers, plastics collectors, and, increasingly, millions of tonnes of imported waste.

Indonesia, like many other East and South Asian countries, is now grappling with a rapid surge of imported waste from high-income countries. China, previously the world’s largest importer of waste, imposed strict and sweeping restrictions on its waste imports in 2018, causing an avalanche of global waste that has now inundated dozens of countries throughout the region.

In Indonesia, this influx of waste has strained the country’s already weak waste management infrastructure. One report estimates between 25 to 40 percent of imported plastic waste in East Java ends up in open fields or is burned, rather than recycled. In fact, just a small portion of imported waste can be recycled, in large part due to poor processing from its country of origin.

Without the resources to properly process its own waste, let alone imported waste, Indonesia has seen its rivers become some of the most polluted in the world, with the Ciliwung River one of the worst among them. Further concerning, an estimated 20,000 items—ranging from plastic bags, bottles, food containers, diapers, tyres, and more—enter the sea every hour from the mouth of the Ciliwung River.These items, as they are taken by the tide, make their way into the Java Sea and are later dispersed throughout the Indian Ocean and beyond. Then, millions of these items—if they are not first mistaken as food by sea life—wash up on the shores of Australia.

Waste management needs a more coordinated approach

The tightening of waste imports by China has prompted a broad review of the practice of countries’ exporting waste, and in Australia revealed a chronic underinvestment in waste processing and recycling infrastructure. Australia has depended for years on exporting its waste to Asia for recycling. Today, however, as more countries throughout Asia are turning away hundreds of containers of contaminated and poorly processed recycled goods, the lack of Australia’s own ability to manage its waste has come front-and-center.

In 2020, following additional import restrictions imposed by Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, Taiwan, India, and the Philippines, the Australian government announced a $190 million commitment toward a broad effort to build the capacity of Australia’s domestic recycling capabilities.

This effort seeks to stimulate private investment in Australia’s waste management industry and already, large manufacturers and companies throughout Australia have announced investments in new domestic recycling facilities and targets.

As Australia bolsters its commitment to the development of a circular economy and phases out its waste exports, a key question remains: What about Asia?

Undoubtedly, Asia will remain entwined in Australia’s recycling industry:

First and foremost, the rapid growth of consumerism throughout Asia will continue to burden underdeveloped waste management industries. Several countries throughout Asia are among the fastest growing economies—and populations—in the world. As the middle class grows, so will the proliferation of retail shops, fast food restaurants, and large department store chains, driving up demand for goods that, historically, has been strongly fueled by a consumer fidelity to all things convenient and cheap. Predictably, waste production will exponentially increase throughout Asia. Without solutions to manage these increases, waste will continue to make its way into the continent’s waterways and into the ocean.

Regardless of its growing domestic waste management capabilities, Australia and its 25,000 kilometers of coastline remain susceptible to the environmental impact of ocean plastic pollution originating from Asia.

In total, half of the world’s ocean plastic pollution originates from only five countries: China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Philippines, and Thailand. Investing in waste management in these countries could reduce the flow of waste into the oceans by 45 percent. Australia can—and should—play a leading role in the development of sustainable, inclusive, and circular waste management industries in Asia, particularly these five countries, to address this crisis. Key investments in new technologies and private sector solutions will be essential in strengthening waste processing and recycling value chains throughout the region and introducing new products that reimagine new uses for waste. These investments, in partnership with coordinated initiatives to build the capacity of waste management businesses and local communities, will significantly reduce ocean plastic pollution over the coming years.

Secondly, the increasing globalisation of economies and businesses has emphasised the need for coordinated efforts toward waste management. Particularly, the growing support of extended producer responsibility (EPR) legislation throughout Europe and Canada will undoubtedly cascade to Australian industries—and their capabilities in serving a growing Asian consumer class.

EPR requires companies to integrate the full “life cycle” costs into the market costs of their products, including the costs associated with waste management and environmental impacts. This will strongly incentivise many global companies, including those based in Australia, to adapt to more environmentally friendly production cycles.

In order for Australian industries to remain competitive in an increasingly global marketplace, waste management in Asia must become an urgent priority. Currently, without proper waste management in many countries, the economic and environmental impacts under EPR legislation could result in exorbitant market costs of products, making business in Asia unfeasible.

More urgently, the growing popularity of EPR legislation is prompting the need for greater investment in private sector recycling infrastructure. Systemic change in how companies produce their goods, as well as how they are recycled and managed after use, will require financial incentives alongside legislative change—a need that the Australian government will undoubtedly face in the future as its companies grapple with the changing global landscape of producer responsibility requirements.

As Australia considers the development of its own waste management infrastructure, it must also take a leading role in the development and modernisation of waste management in Asia. By doing so, Australia will not only help reduce the waste that arrives on its shores, but it can also facilitate innovation in waste systems in Asia through investment, technical assistance, and transfer of important technologies in recycling and waste management.

Cleaning up in Asia is disjointed and dangerous

Throughout Asia, waste management remains largely disjointed and comprises informal networks of independent waste and recycling facilities. Without proper oversight and regulations, these facilities often do more harm than good to their local communities: chemical-laden run-off seeps into local waterways after plastic is melted and processed, while remnants of products that cannot be recycled are burned or dumped; workers, too, in these facilities face perilous conditions, often operating burners that melt plastic at upwards of 200 degrees Celsius without protective equipment.

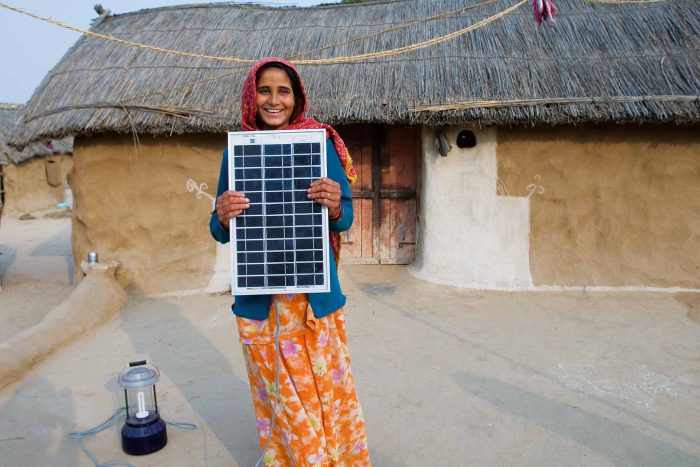

Waste collection is also largely informal. Typically, in low-income communities, waste collection relies heavily on women, most of whom view waste collection as a way to earn small amounts of income while still caring for their children. This, however, compounds their vulnerability and perpetuates systemic inequalities that exclude them from opportunities for growth. Most women earn extraordinarily low wages—lower than their male counterparts—from waste collection, which often can be hazardous for women and their children. These women are also unlikely to have proper national identification records, which structurally excludes them from government safety nets and services, like healthcare.

In Asia, improving waste management will require a broad and inclusive strategy that addresses the realities of the informal waste management sector while strengthening its capacity and standards. In fact, the strategy for Asia should strongly mirror Australia’s own strategy for developing its domestic waste management capability: (1) catalyse private sector investment while (2) facilitating an enabling environment that supports local communities and governments to manage and grow waste management solutions.

The Incubation Network, an organization established by The Circulate Initiative and SecondMuse, is specifically working to implement this dual strategy to curb the tide of ocean plastic pollution originating from South and Southeast Asia while creating economic opportunities for affected communities.

Step one: unlocking the capital for a new approach

Throughout South and Southeast Asia, waste management is currently heavily subsidised by local governments, accounting for a disproportionately large portion of their budgets. Unlike in Australia, few private sector actors, if any, are currently investing in waste management facilities or solutions.

Ocean Conservancy estimates that developing the waste management industry in this region will require an estimated US$50 billion over the next 10 years. Local governments alone will be able to meet only a small fraction of the total investment needed, underlining the urgent need for private capital.

Given that the waste management industry throughout much of Asia is still nascent, venture capital will be required first, before attracting broader, institutional funding. Patient capital, provided by investors willing and able to absorb some risk, can help incubate waste management solutions by unlocking much-needed capital to invest in small businesses and technologies. In turn, these businesses can make the investments they need to demonstrate their viability to the broader industry.

Nepra, a waste management company in India, offers a tangible example of a locally developed waste management solution that benefited from early-stage investment back in 2013 from Aavishkaar Capital. With access to capital, Nepra has been able to develop technology-driven processes to connect all stakeholders along the waste management value chain in several western districts in India. Nepra’s people-centric business model connects informal waste collectors to recyclers and other businesses, while ensuring recycling businesses can source quality materials and other waste is disposed for energy recovery. In November 2020, Aavishkaar Capital and Circulate Capital announced an additional $18 million investment in Nepra to help it scale its proven model to additional geographies.

Nepra, along with Tridi Oasis and Lucro, are the first waste management companies to receive investment from the recently launched $100 million fund from Circulate Capital. The fund is exclusively dedicated to incubating and financing companies throughout South and Southeast Asia that help prevent ocean plastic pollution through improved waste management.

As more early-stage investors help incubate and grow more waste management companies throughout the region, Australian institutional investors will soon have more opportunities to help scale this work.

Step two: a new ecosystem is needed for success

In addition to capital, the success of emerging waste management innovations rests on the inclusivity and support of the broader enabling environment. Piecemeal technical solutions, while important, rely on a broader ecosystem to function properly. Government agencies, local municipalities, businesses along the value chain, as well as informal workers and businesses, all must be included and engaged in the development of waste management sectors.

An inclusive, ecosystem-wide approach will ensure that linkages between waste collection, aggregation, processing, and distribution are coordinated; regulations and oversight certify that waste management and recycling practices are protecting people and the environment; and, just as importantly, those most affected by the current waste crisis—vulnerable women, their children, and their communities—are included in and benefit from the sector’s growth.

The Incubation Network is particularly focused on fostering inclusive waste management ecosystems in South and Southeast Asia and has outlined several strategic priorities to successfully facilitate enabling environments.

First, networks need to be developed to connect local, emerging ventures to mentors, technical assistance, and ecosystem partners. This helps fortify the impact of early-stage private sector investments in waste management businesses and technologies by connecting them to the non-financial support and partners they need to scale.

Second, ideas for ecosystem-wide interventions should be tested and piloted to identify key bottlenecks within particular value chains. By understanding value chains in their entirety, targeted solutions can be developed that adequately address communities’ needs in sustainable and inclusive ways.

Lastly, underpinning all of this work is the meaningful engagement of vulnerable women and community members. The development of sectors like waste management through global markets and capital-based solutions are prone to perpetuate and reinforce patterns of power, privilege, and biases. Women trash collectors are the most likely to be left out of the sector’s growth as they comprise the informal—and too often unseen—participants. Engagement of informal stakeholders, especially the most vulnerable, will help transform their work into more productive, income earning enterprises, which then fuels the growth and development of the entire sector.

In India, The Incubation Network is supporting Saahas Zero Waste to work with informal waste entrepreneurs in India to help formalise their businesses. The project aims to provide safer more profitable working conditions through business training, accreditation, and access to better prices for the materials they collect. Over time, the project aims to develop a revolving loan fund that, together with the training and accreditation, could lead to the professionalization of hundreds of thousands of waste entrepreneurs in India. These initiatives are crucial in building the capacity of local waste management environments, which helps catalyse the impact of capital investments in the private sector while including the most vulnerable groups in the sector’s development.

Policy implications for the future

For Australia, waste management will continue to emerge as an urgent domestic priority, as well as an urgent foreign policy initiative to mitigate ocean waste affecting Australia’s shores and sea life. Along with plastic, food waste has also come into sharp focus and prompted calls for a rethink on how waste should be viewed as a resource.

The volume of plastic packaging alone is projected to drastically increase over the next few decades, reaching an estimated 318 million tonnes produced by 2050—which is more than the total volume of all plastics produced today. Australians alone throw away 65 kilograms of plastic per person, per year. The growth of Asian consumerism will likely soon match this rate, exacerbating the environmental crisis of ocean pollution.

Without significant action, plastic will continue to leak into the ocean at increasingly alarming rates. In addition to the increasing pollution of seas and beaches around the world, sea life will continue to ingest harmful waste, which is leading to the prevalence of microplastics throughout global food chains.

Eight million tonnes of plastic will enter the ocean this year—a projection that is estimated to double by 2030. The debris reaching Australia’s shores will also grow more severe, given its proximity to Asia, where the majority of ocean plastic originates.

As Australia works to invest in a more responsible and circular economy domestically, it must also weigh the ramifications of the waste management crisis in Asia—a crisis fueled by decades of harmful waste exporting practices by high-income countries like Australia. For Australia, a key foreign policy objective must include solutions that incentivise venture capital to help incubate and scale waste management solutions throughout Asia, as well as investing in facilitating environments that foster and support the development of inclusive, sustainable, circular economies that protect people and the planet. This can come in the form of matched contributions and tax incentives.

Simon Baldwin is the Director Singapore Hub at SecondMuse and Rob Hulme is Asia Director at Beanstalk Agtech